Real Life Rock Top Ten: All-Bob Dylan Edition

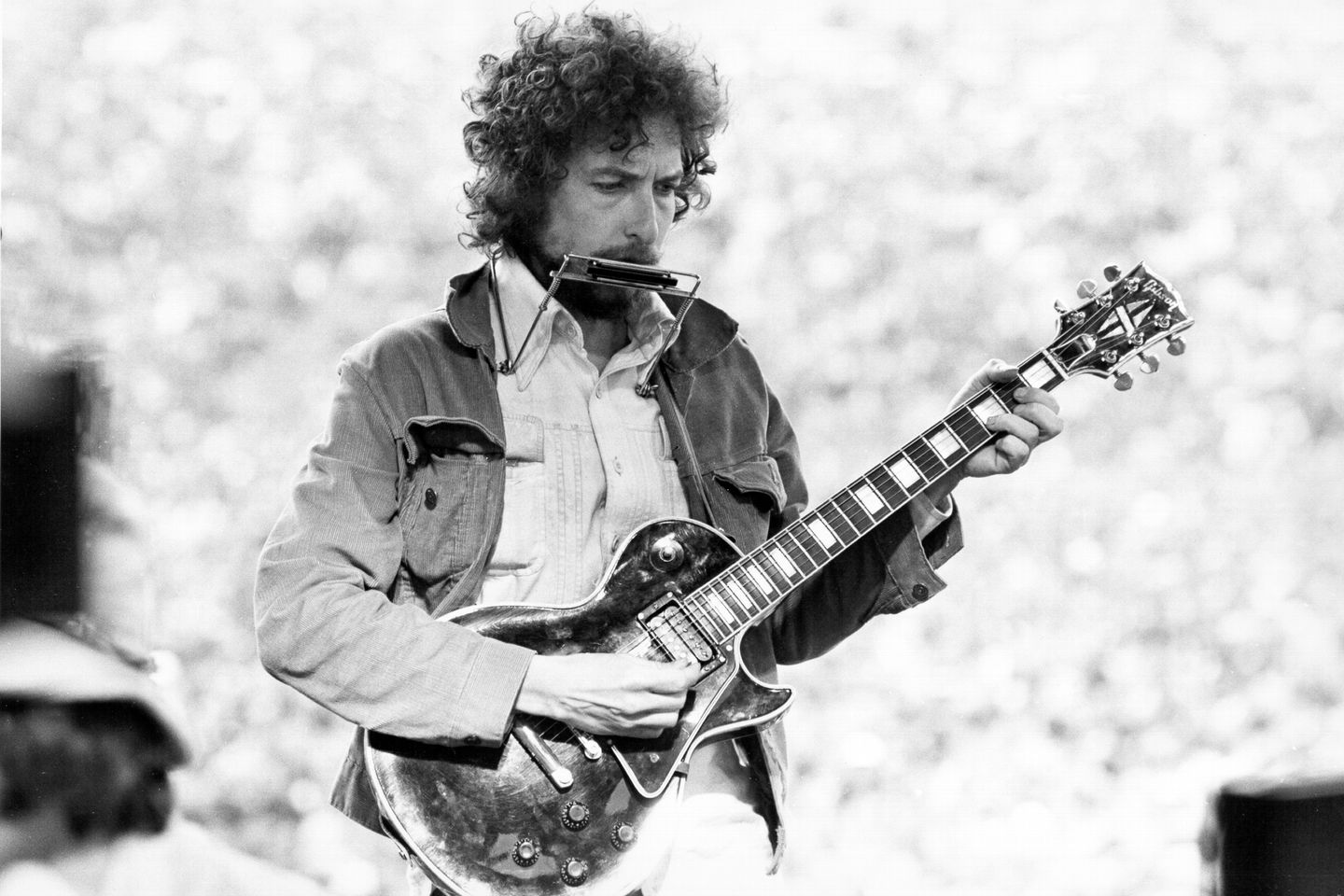

Bob Dylan performs at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco, California, March 23, 1975.

Alvan Meyerowitz/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“Real Life Rock Top Ten” is a monthly column by cultural critic and RS contributing editor Greil Marcus.

1. “Nobel Prize winner Bob Dylan plays River Spirit Casino Resort,” Tulsa World (October 13th). Though it does carry an echo of the Cheek to Cheek Lounge of Winter Park, Florida, where in 1986, after a show by a reconstituted version of the Band, pianist Richard Manuel went back to his motel and hanged himself, better this than the White House. I hope he wore his medal.

2. Bob Dylan, More Blood, More Tracks: The Bootleg Series Vol. 14 (Columbia Legacy, November 2nd). The six-CD, 87-cut set — complete recordings in New York in September 1974, some with Eric Weissberg’s Deliverance band, mostly solo or with bass accompaniment, and the five surviving numbers made in Minnesota three months later with local musicians— is the only way to go if you want to hear what the 1975 Blood on the Tracks almost was, and how it was saved from itself. Suspect aspects of an album that has been overpraised and over-fetishized for more than 40 years are made clear. The fetishism is devoted to the New York sessions, which at one point resulted in a finished-album acetate that was circulated and then bootlegged. Especially once the Weissberg outfit was out of the room, with their eight consecutive takes on the stupid hoedown “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome when You Go” — yeah, that’s a real heartbreaker of a breakup song, especially if you can’t remember the name of the person you’re supposedly breaking up with — the New York performances are pure, real, acoustic, searching, pure, anguished, soulful, unencumbered and pure. You can see right through them, to the person who’s singing! It’s like reading his autobiography! This is the truth!

It’s also, with many exceptions — when a song that seems to be fading away is found, sometimes only for a moment — tiresome and monotonous. It’s not the boredom of sitting in a studio listening to someone do a song over and over until it’s right. It’s the songs themselves that bring these qualities to the surface. Though there are lyric changes here and there — most noticeably the “Tangled Up in Blue” verse “He was always in a hurry/Too busy or too stoned/And everything that she ever planned/Just had to be postponed/He thought they were successful/She thought they were blessed/With objects and material things/But I never was impressed” which luckily didn’t make the transition from New York to Minnesota — these numbers are very carefully crafted; in terms of their formal parts they’re all but nailed down from the start. They’re so crafted that a certain slickness curdles the most well-made of the tunes. Five of the 10 songs on the Blood on the Tracks album (plus the sharp “Up to Me,” left off but released much later on the Biograph compilation) work off tag lines: the coy device where the title of the song is also the last line of every verse. The song has to fit itself, and often it can’t breathe. You might hear this most vividly in “Shelter from the Storm.” Everything is in perfect balance. The lines “In a little hilltop village/They gambled for my clothes” seem almost biblical. But listen too closely, and it begins to sound far too contrived, and the emotion begins to feel phony. “ ‘Come in,’ she said, ‘I’ll give ya/Shelter from the storm’” — would any real person give that too down-home “ya” such a jocular lift? This is less bad singing than bad acting — and if you start to hear it this way, that “gambled for my clothes” feels much too self-consciously mythic, and of course it would have to be in a little hilltop village, instead of Eighth Avenue, where in 1974 people probably did gamble for their clothes. Maybe the true story in this set comes in those takes when you can hear Bob Dylan slide away from the songs, when you can hear him give up ownership of them, listen to them, and hear the songs tell him how they want to be played.

For me, the great drama comes with “Tangled Up in Blue.” The first time Dylan tries it (Disc 3, Track 1), in New York, with only Tony Brown on bass at his side, it’s in a drawl with words cut off, somehow the essence of hard-boiled. Musically it’s a mess, it wears out, but as with any hard-boiled detective novel you want to know what happens next. Is that why the song is so appealing, one long, snaking, beckoning finger? That feeling is there from the start. Then after two takes of “You’re a Big Girl Now,” there’s a confusion of attitudes, the perspectives of the “he” and the “I” almost not so much tangled as random, with the song not talking but organ from Paul Griffin loosening it up, trying to find room in it (Disc 3, Tracks 4-5). After five takes on other songs, they try it again (Disc 3, Track 11), looking for momentum. The song is falling short of itself. You can hear it; you can almost hear the musicians hearing it, but the charm of the song, the story it’s throwing out in pieces that don’t exactly match, with then and now and a farther then so scrambled that a swirling, all-encompassing present dissolves its riddles, is always there. On the last of the four days of New York sessions, 14 songs in, Dylan and Brown go after it again, three times in a row (Disc 5, Tracks 1-3). The first time is a breakdown, but before they put the song back together a faraway, completely different melody rises out of the song, a reverie, as if the singer is for a moment not telling a story but remembering it in a dream. It’s stunning — a glimpse of another world in a closed book. And they try again, in the last moments of the last New York day (Disc 6, Tracks 2-3). First there’s a wordless vocal, and then the voice is strong, confident, aggressive, coming down on “In the 13th cen-tury” as if the last syllables are an inside joke. And it’s still a sketch.

In Minnesota, with guitarists Chris Weber and Kevin Odegard, keyboard player Greg Inhofer, mandolinist Peter Ostroushko, bassist Billy Peterson and drummer Bill Berg, the music explodes — you can hear the songs getting what they wanted. In New York, “Idiot Wind” was an essay; here it’s a tornado, leveling a whole town and then coming back to destroy anything it missed the first time around. “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts,” which in New York was a ballad, is now the big crowd-pleaser at the Virginia City opera house in 1878. And “Tangled Up in Blue,” with the band playing hurdy-gurdy, carries the thrill you get at a show when the band hits the first note of the song you came to hear, a song you’ve heard hundreds of times, the thrill of hearing something that’s become part of you, less part of your mind than your reflexes. It’s as if the new musicians were there for all the previous attempts at the songs, carrying with them the frustration of not getting it into the take (Disc 6, Track 6) that will be the claim of these unknown, forgotten people on history, on time. With the song underway, Berg makes a tap, and you can feel the hesitation, not his, but the song’s, and then a final determination, a wrangler saying, “All right, ’round ’em up, we’ve waited long enough.”

The result is joyous. Dylan sounds like he’s singing with whips. He tears through the story, tearing it up as he goes, dropping the pieces like Hansel’s bread crumbs, circling back, plowing them under, leaving another trail. The performance builds up a momentum, never rushed but unstoppable, with Dylan singing and the band members playing as if they can’t wait to get to the end, not to get it over with, but in an anticipation of how satisfying it will be when the song, finally, finishes itself. It’s music where the fanfare comes at the end — the only song on Blood on the Tracks with a classic ending. The three hard breaths: two short, one long. An exhalation that says the last word as if it were the first.

Like all the master takes that eventually made up Blood on the Tracks, it sounds different from what you’ve heard before, even if you’ve heard the album those hundreds of times. As it was released in 1975, the record was washed with echo; here that’s gone. You don’t hear a fated work of art; you hear people trying to get something done.

3. Heaven’s Door Tennessee Straight Bourbon Whiskey (Heaven’s Door Spirits, Columbia, Tennessee). The striking bottle comes emblazoned with one of Dylan’s ironworks designs, and despite the odd name — drink this and die? — what’s inside lives up to it. It’s rich, full, most of all smoky. You can’t taste it all at once. It seems to change from sip to sip.

It reminded me of the bourbon my grandfather Isaac Gerstley made in Philadelphia before Prohibition — Rosskam Gerstley & Co. Old Saratoga. With friends, we did a taste test, and no, Heaven’s Door’s three or four levels didn’t match the ladder of sensations floating in the dark thimbles of Old Saratoga. But Heaven’s Door, the label says, “is aged for a minimum of 6 ½ years.” Old Saratoga has passed a hundred. What if Heaven’s Door makes it that far, well after Bob Dylan and anyone else alive to try it now will be beyond knowing if it did or not?

4. Todd Alcott, “Mid Century Pulp Fiction Cover Project” (openculture.com). After reimagining songs by David Bowie, Elvis Costello and others as cheesy paperbacks, most of Alcott’s Dylan works don’t tease anything out of the songs, they flatten them: His “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” is less about the song than a new cover for J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World. But he scores with a knockoff of the Now-a-Major-Motion-Picture 1940s and ’50s covers capitalizing on movies made from such 1930s Erskine Caldwell Southern sex ’n’ soil bestsellers as Tobacco Road and God’s Little Acre: “Maggie’s Farm” recast as a 25¢ number featuring a bare-chested hunk at his plow wiping the sweat off his neck with a red polka-dot bandanna and a dark-haired woman in boots and an unbuttoned white blouse sitting on a log nearby. She’s giving him the eye; he’s wondering whether to take her up on it now or later. As I remember, that wasn’t exactly the song.

Credits: Courtesy of The Mid-Century Pulp Fiction Cover Project, Pan Books Ltd.

5-8. Bob Dylan, Live 1962-1966: Rare Performances from the Copyright Collection (Columbia Legacy). Twenty-nine tracks on two discs; often when the passion rises out of a performance it’s so intense it can be hard to credit. Sometimes it’s a matter of craft, as on “Seven Curses” (New York, 1963), an original song cast as a Child Ballad: the beginning is so arresting you’re sucked in in an instant, transported back hundreds of years, to times when events turned into fables. “When the judge saw Reilly’s daughter/His old eyes deepened in his head” — you can feel the writer inhabiting both the woman and the man, the tension is already building, and the final countdown of curses comes on like Dracula descending a staircase, from the prosaic “That one doctor will not save him” to the supernatural: “And that seven deaths shall never kill him.” With “It Ain’t Me, Babe” (London, 1964), it’s the singer reaching through a song to grasp something that seems beyond words and music. With “Mr. Tambourine Man” (London, 1964), it’s the play of melody, the way Dylan slows down the harmonica solo in a way that the shifting sound so completely creates its own ambience you don’t care if he ever gets back to singing the song. And there is the force and brutality and scorn in the last verse of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” (New York, 1963), as if to disguise the singer’s own shock at his own tune — it’s horrifying, and when the crowd applauds at the end of the song it feels all wrong, a violation, as if the audience thinks the song was congratulating them, as if when Dylan sings “Those who philosophize disgrace,” he’s talking about someone else. Did he ever put more into this song? Did the song ever get more from him? Compared to this, “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” (London, 1964) is a dog braying.

9. Bob Dylan, “I Got a New Girl” (YouTube). From 1959, at a friend’s house in Hibbing. Though the words are too obvious for any professional recording, the feeling is very Bobby Vee. “Suzie Baby ,” not “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes.”

10. Laurence Osborne, Only to Sleep: A Philip Marlowe Novel (Hogarth). Osborne has to do a little cheating to get the 73-year-old retired private eye into 1988, but not more than Raymond Chandler himself did, who in seven mysteries from 1939 to 1958 had Marlowe born anywhere from 1903 (for The Big Sleep, his first) to 1914 (for Playback, his last). The payoff is the chance to listen in as Marlowe muses on “the strange music of Tina Turner,” shakes his head over Guns N’ Roses, and sets a scene that in its very blankness carries a hint of something uncanny, telling the reader something about the characters that they don’t know themselves:

When I was opposite the gangplank I saw that it was not a party at all but just a middle-aged man with a Mexican girl and a boat’s captain of sorts in a cream-colored uniform. The middle-aged man — Black, I assumed — had a sunburned pirate’s face with a ridiculous dyed goatee and eyebrows painted on with a calligrapher’s brush. The man fighting signs of aging always has a touch of sinister vaudeville about him. But his threads were impeccable. The three of them were playing cards at a glass table with a bottle of Jav’s rum and listening to Bob Dylan.

It’s a literary impersonation that actually works, even if Osborne has Marlowe say “It is what it is” once and “Back in the day” at least twice — the kind of cant phrases Chandler would have never used, because they smear specifics of motive, mood, time and place and replace morality with Whatever. I hope there’s a sequel. Seventy-three is not that old, and “I stopped the car to let a tarantula make its way across the road in the same way you would stop for an old lady” is just what a 73-year-old Marlowe would say.

Original Article: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/real-life-rock-top-ten-746600/